Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell

You’d think, in 2012, being gay wouldn’t be an issue anymore. You’d assume, given the Mardi Gras has worked its way from a protest march to a mainstream festival celebrating homosexuality, that there was a general acceptance in the community. You’d be forgiven for thinking – the occasional bigot and ideologue aside – we’d gotten to the stage where we are willing to live and let live.

And maybe you’d be right – there’s even movement at the station on gay marriage, after all.

But there’s one part of society where all movement seems to have ground to a halt. Let me ask you a question – how many gay Rugby League Players, past or present, do you know? How many gay AFL players? Well, by my reckoning the number stands at one in the NRL, zero for AFL. That’s one person in the entire history of both games. It is a curious statistical anomaly. There are hundreds of first graders in each code running around the park this season. By the law of averages, there would have to be a few dozen gay or bisexual players.

It doesn’t need to be hidden. Listen to this respected sports journalist speaking about that one gay Rugby League player: “he’s been treated with great respect,” and "football is a very egalitarian game, It's a workingman's sport that has been open to all clolours and creeds for years." And finally, “people who play the game understand society has changed a bit now and are more accepting. It’s all been quite heartening, really.”

Which all sounds pretty reasonable, with the exception of one important thing: the journalist (Ian Heads) was speaking about Ian Roberts. In 1995. Not a single player has identified himself as gay since.

Let’s look at that statistical anomaly for a moment. For the general population, estimates of homosexuality in men vary from about 3 to 9 per cent, depending on what study you believe. So let’s split the difference and say about 5 per cent. At an educated guess, the NRL in the last seventeen years would have seen around 1500 players cycle through first grade. Which means around seventy-five players over that period would have been gay. That’s seventy-five players who have felt the need to disguise who they are from the public eye. Yes, of course, there may be some out there who have told close friends and family, who don’t want to make a public statement out of it. That’s understandable. But really – not one in all that time to come out publicly? Something doesn’t smell right.

Sure, professional male sport very macho. And it makes sense that this will be one of the final frontiers for tolerance of something perceived (by some) as being particularly un-macho. Nonetheless, the ‘don’t’ ask – don’t tell’ policy in men’s sport has reached its used by date. The current position was best articulated by Jason Akermanis in 2010 when he said, “…I believe the world of AFL footy is not ready for it… I know there are many who think a public AFL outing would break down homophobia, but they don't live in football clubs. It's not the job of the minority to make the environment safer. Not now, anyway.” He went on argue that it would bad for the gay players if they came out – that they’d be ostracised and so forth. In essence, he was arguing they stay in the closet for their own wellbeing.

Well, call me cynical but Mr Akermanis seems like a concern troll to me. A ‘concern troll’, by the way, is the term for a person who feigns worry about an issue (football players not being accepted in the team when they come out as gay) in order to pursue their own agenda (ensure no-one comes out and changes the status quo). Sort of like Tony Abbott saying “I am worried about Craig Thomson’s mental health – he should quit parliament”. Concern troll.

Well here’s the thing: not even the American military subscribes to ‘don’t ask don’t tell’ anymore. That ended in 2011. You know there’s a problem when the Marines hold a more progressive position than you. As a fan, it’s disappointing that the idea of manhood around both sports continues to be so one-dimensional. I reckon men like Roberts do a lot more for the game than men like Willie Mason. This isn’t about being radical or trying to push boundaries. This is about reality. Or in the case of AFL and NRL, the ongoing denial of reality.

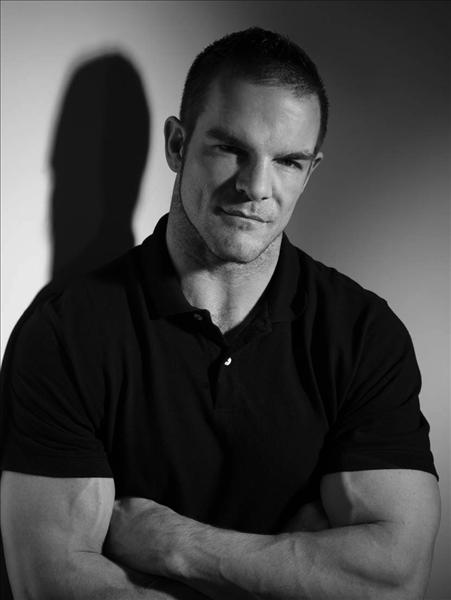

A player coming out would not “break the fabric of a club” in the words of Akermanis. When Ian Roberts came out in 1995, it didn’t affect his career. He appeared on the cover of gay magazines naked, he was star attraction at the Mardi Gras. He couldn’t have been any more overtly gay if he tried. Yet after he came out he still represented Australia and the Blues in State of Origin.

And it was good for the image of the game. Here was a down to earth man’s man, totally comfortable with who he was. Roberts said: “I’m comfortable with my life every day of the week. People should get over it and get on with their own lives.” More importantly, for young gay men it gave them hope. For many, who were inspired by Roberts, it was life changing. One of those inspired was Matt Cecchin, NRL referee who came out publically about his sexuality this year, who said he only did so after reading Ian Robert’s book, Finding Out.

Since Cecchin came out, not a negative word has been said. Cecchin has said that he has never – ever – been sledged once for his sexuality by a player or NRL official. Of course, his ability as a ref was sledged after the Blues were robbed in the first State of Origin, but that was bloody well deserved.

The NRL and AFL are both big enough and tolerant enough to accept gay players. For the most part, I’d be surprised if the player coming out got anything other than support from team-mates and the media. The vast majority of the fans would be supportive. The ‘coming out’ – as with Roberts and Cecchin – would pass without too much controversy.

The big deal is going to be for those young closeted blokes, who would suddenly feel a lot less depressed, a lot less ashamed, and maybe even strong enough to come out to friends or family. Or even teammates. They shouldn’t be ashamed. It’s 2012, after all.